19

quindici e più anni di abbandono.

Il complesso, costruito nel 1912 e

successivamente modificato, è

composto di tre blocchi edilizi

distinti; la palazzina d’ingresso

dalla città (corpo di fabbrica A), un

primo grande fabbricato, a suo

tempo destinato a detenzione e

uffici (B), un edificio di forma

lineare che si protende verso le

mura della città, anch’esso deten-

tivo (C); accanto a questi erano

sorti nel corso dei decenni ulteriori

edifici; come ovvio, tutto è rac-

chiuso da una doppia cinta di

muri. Con Decreto del Soprinten-

dente Regionale del 16/9/2003 l’ex

carcere circondariale è stato dichia-

rato d’interesse culturale e per-

tanto sottoposto alle disposizioni

di tutela ai sensi della legislazione

vigente, «in quanto […] caratteri-

stico esempio di edificio peniten-

ziario del primo Novecento».

Ecco dunque un primo tema su

cui ragionare e compiere scelte:

quali valori individua la dichiara-

zione di tutela? È davvero d’inte-

resse questo complesso? Lo è per

intero, nel suo insieme, o si può

stabilire per i corpi di fabbrica un

diverso livello di qualità architetto-

nica e di significato per la tipolo-

gia carceraria, oggettivamente

riconoscibile? Il quesito non è

certo casuale: infatti da molte

parti si sono levati dubbi, anche in

tempi recenti, sulla opportunità di

collocare il museo, istituzione a

finalità pubbliche per eccellenza,

all’interno di una struttura, come

quella in esame, con caratteristi-

che di poca flessibilità, severa

nell’organizzazione spaziale, bloc-

cata nel rapporto interno/esterno

e in quello tra i diversi edifici;

tanto più poi un museo come il

MEIS, concepito come spazio

rivolto all’incontro ed all’integra-

zione, aperto ai visitatori e alla

città, fatto per produrre cono-

the former county jail of cultural

interest

and therefore under protection

according to the law in vigour, “in

as much as it is a […] typical example

of an early Twentieth Century

penitentiary building.”

This, therefore, was the first criteria

that we had to consider when

making decisions: which are the

characteristics that need to be

preserved? How important really is

this complex? Is it for the complex

as a whole, for the collection of its

parts, or should one identify

which buildings are architecturally

significant and which are significant

as an example of a jail? The

question is not one to be taken

lightly, as there are grave doubts

even now, as to the feasibility of

placing a museum, which is

quintessentially a public institution,

within a structure such as this, as

the inflexible physical constraints

restrict options for spatial

organization. A museum like the

MEIS is conceived as a space for

meetings and integration, open

to visitors and the city, made to

raise awareness and disseminate

information through events and

displays. These are legitimate

doubts, which lie behind the

willingness to give life to a museum

that is able to maximize the

architectural potential of its

function while yet being concerned

that this new function may in some

way alter those unique elements of

the preexisting complex, thereby

detracting from our cultural

heritage.

Finding the answers to these

questions requires a detailed

knowledge of the complex,

beginning with an in-depth analysis

that strives to understand, without

prejudice, the inherent quality of

each building rather than focusing

on reconciling the building with its

18

di film e di spettacoli sui temi della

pace e della fratellanza tra i popoli

e dell’incontro tra culture e reli-

gioni diverse».

Del 23 gennaio 2007 è l’atto costi-

tutivo della Fondazione MEIS, che

nasce con “finalità di gestione,

valorizzazione, conservazione e

promozione del

Museo Nazionale

dell’Ebraismo Italiano e della

Shoah

”, e che in sostanza è l’orga-

nismo al quale è demandato il rag-

giungimento delle finalità della

nuova istituzione museale, rego-

landone le modalità organizzative.

Della Fondazione fanno parte Il

Ministero per i Beni e le Attività

Culturali, il Comune di Ferrara, il

Centro di documentazione ebraica

contemporanea (CDEC), l’Unione

delle comunità ebraiche italiane

(UCEI).

Fin dal 2003, alla realizzazione

della sede del museo sono stati

destinati 15 milioni di euro, men-

tre al funzionamento è stato asse-

gnato un contributo di 1 milione

di euro l’anno, fondi che tuttavia

si sono resi effettivamente dispo-

nibili solo con la legge 10 ottobre

2005, n. 208. Secondo gli accordi

nel frattempo intervenuti tra le

amministrazioni interessate, al

Comune di Ferrara spettava indivi-

duare la localizzazione dello spa-

zio in cui costruire la sede del

nuovo museo, mentre al Ministero

per i Beni e le Attività Culturali la

realizzazione dell’edificio: su que-

ste basi in un primo momento,

quello relativo al Museo della

Shoah, il Comune aveva messo a

disposizione un’area di circa 10

mila metri quadrati sita a nord

della città storica, nel Parco

Urbano dedicato a Giorgio Bas-

sani. Ma il sostanziale cambio di

rotta relativo alla missione del

museo e la sua nuova caratterizza-

zione consigliava un luogo interno

alla cerchia delle straordinarie

mura di Ferrara, a contatto con la

città ed i percorsi ebraici in essa

significativamente presenti.

La scelta cade sul complesso edili-

zio dell’ex carcere circondariale in

via Piangipane, di proprietà sta-

tale, che il 29 novembre 2007

viene consegnato dall’Agenzia del

Demanio al Ministero per i Beni e

le Attività Culturali per essere

destinato al Museo dell’Ebraismo

Italiano e della Shoah. Nel corso

dell’anno successivo la Direzione

Regionale dell’Emilia-Romagna,

Soprintendenza per i Beni Archi-

tettonici e per il Paesaggio e il

Comune di Ferrara danno vita ad

gruppo di lavoro tecnico che

opera da un lato al recupero archi-

tettonico della palazzina d’in-

gresso dalla città, ancora in corso,

dall’altro allo studio approfondito

della consistenza del complesso

ed alla successiva stesura del

bando di progettazione.

Il sito, il museo, il concorso

Il carcere è un luogo per defini-

zione chiuso al mondo, confinato,

fatto per la segregazione: trasfor-

marlo in un museo è la sfida che si

è voluta cogliere, pur nella consa-

pevolezza delle molte difficoltà che

questa scelta avrebbe comportato:

in prima istanza l’edificio, le sue

caratteristiche architettoniche, lo

stato conservativo determinato da

Ministry of Cultural Heritage and

Activities (MiBAC), the Comune of

Ferrara, the Jewish Contemporary

Documentation Center, and the

Union of Jewish Italian Communities

are all members of the Foundation.

Since 2003, 15 million Euros have

been allocated for the creation of

the museum, with an additional 1

million Euros annually for operating

costs, although these funds were

only approved by law number 208

on October 10th, 2005. According

to the original agreement reached

between the parties, it was up to

the Comune of Ferrara to identify

the site where the new museum

would be built, and to the Ministry

of Cultural Heritage and Activities to

construct the building. Based on

the original plan to build a

Holocaust Museum, the Comune

had selected an area of about 10

thousand square metres situated in

the north of the historical city, in the

large urban park named for Giorgio

Bassani; but with the marked

change of course regarding the

focus of the Museum, a different

site was required, and the seat for

the museum was moved to a

location within the walled part of

Ferrara, placing it in direct contact

with the city and the areas with a

significant Jewish presence.

The choice fell on the site of the

state owned former jail on via

Piangipane. On November 29th,

2007, the property was ceded to

the Ministry of Cultural Heritage

and Activities by the Agenzia del

Demanio

(the

government

department which manages state

owned property) for the purpose of

redeveloping it for the new Museo

dell’Ebraismo Italiano e della Shoah.

Over the following year, a technical

working group was established

with members from the Regional

Directorate for Emilia-Romagna, the

Superintendent of Architectural

Heritage and Landscapes and the

Comune of Ferrara. Their job had

two goals: the first being the

restoration work on the entrance

building, which is underway, and

the second, following an in-depth

study on the overall building

complex and to set up the terms of

competition.

The site, the museum,

the competition

A jail is a place which is by definition

closed to the world, confined, built

for segregation. Transforming such

a place into a museum is the

challenge that we are facing, fully

aware of the difficulties inherent in

the undertaking, beginning with

the building itself, its architectural

features, and its condition after over

15 years of abandonment.

The complex, built in 1912 with

later renovations, is composed of

three separate blocks: the entrance

building on via Piangipane (block

A), a large building that in its day

was used for offices and holding

cells (block B), and a long building

at the back by the walls which also

contained cells (block C). Over the

years other buildings were added;

and obviously, the entire complex

is enclosed within double

surrounding walls. By decree on

September 16th, 2003, the

Regional Superintendent declared

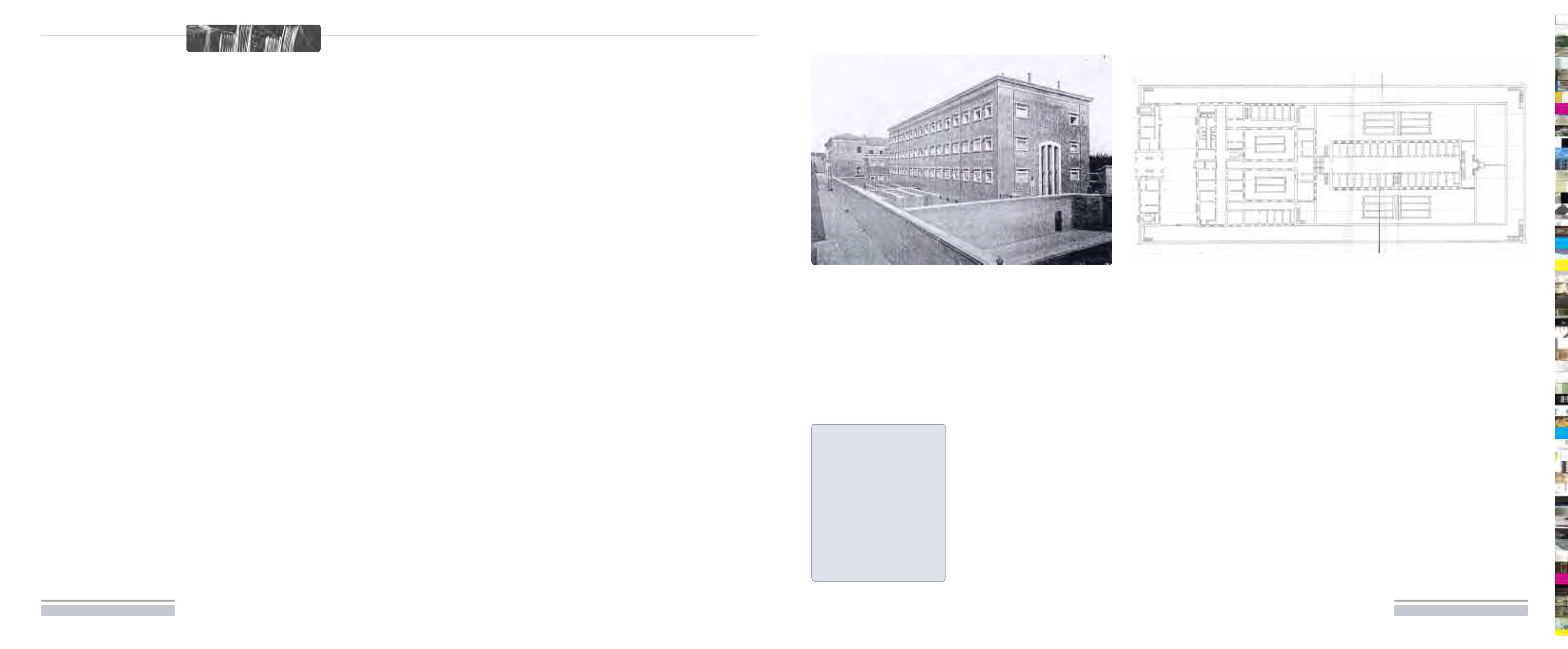

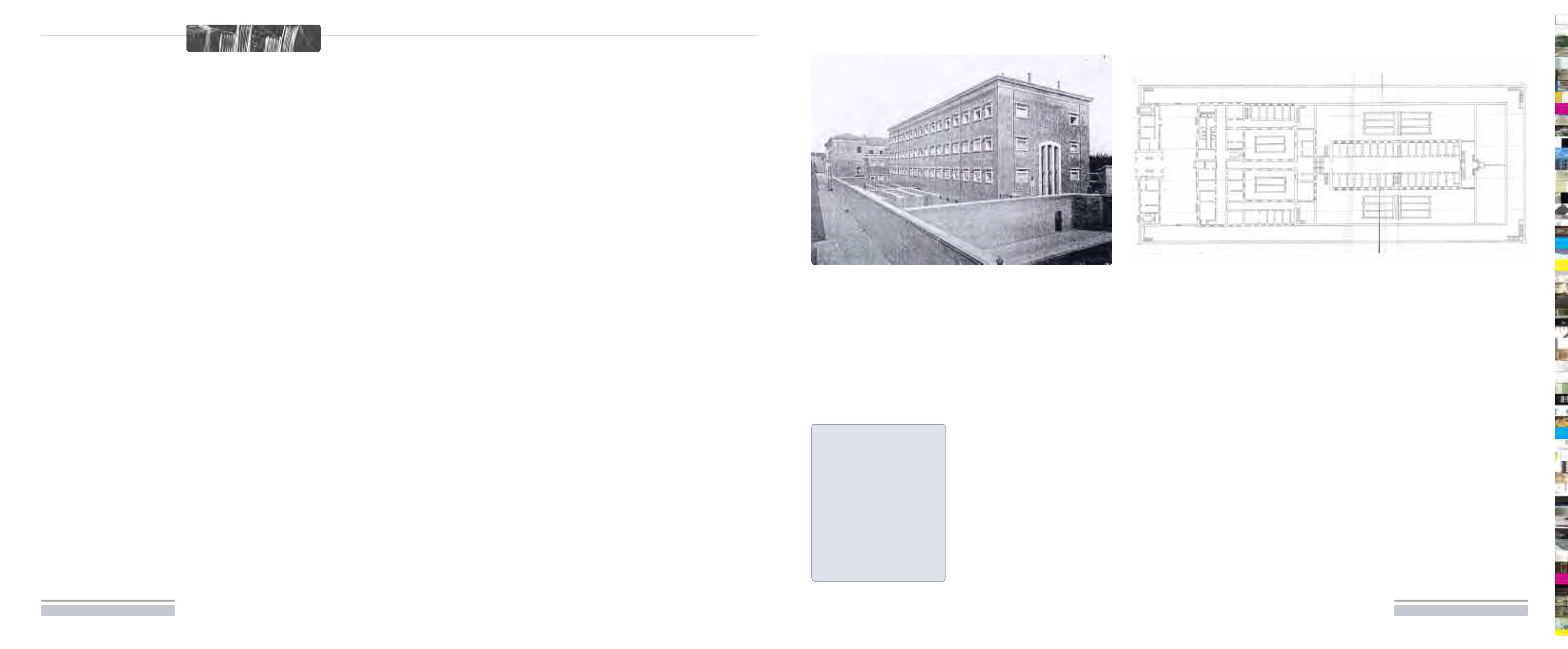

Fotografia e pianta del

complesso carcerario.

Annuario statistico del Comune

di Ferrara, 1912

Photograph and Map of the jail

complex. Images taken from

the Statistical Yearbook,

Comune di Ferrara, 1912